How Long Will We Keep Using Helicopter Surveys?

Isn’t it time we put safety ahead of tradition in aerial inspections?

OK, yep, we’re biased because we like to think of ourselves as a disruptive force in the aerial inspection and aerial survey sector. But really, how many more manned aviation incidents do we need before we start to close the book on helicopter inspections and surveys?

The recent crash of an EC225 Super Puma helicopter in Norway, killing 13 people onboard, highlights the fact that even with the best of design and the best of maintenance, helicopters are far more likely to cause serious accidents, injuries and deaths than remotely piloted aircraft.

Admittedly, moving relevant survey and inspection work from helicopters to UAVs would not entirely eliminate the risk of helicopter accidents, injuries and fatalities, but everything we can do to reduce these incidents is surely a step in the right direction.

Interestingly (and sadly) this tragic crash had a strong connection with Australia as the cause of the crash is thought to be a gearbox failure, and 12 months earlier the gearbox that was installed in this aircraft was involved in a pre-delivery incident in Western Australia when the truck carrying the gearbox swerved to avoid kangaroos and rolled over. The gearbox showed obvious damage and was returned to Airbus Helicopters for inspection and repair, but was subsequently released to be installed in the EC225 in Norway. We can’t place the blame for the crash on that incident, but it will presumably form a large part of the investigation.

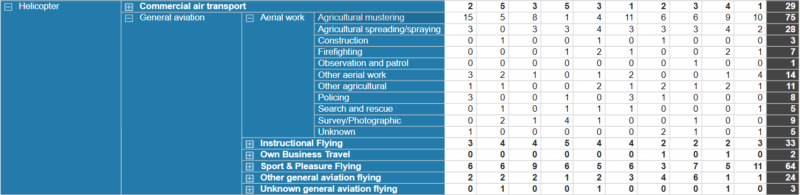

This chart, from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), shows that between 2101 and 2019 there were almost 200 incidents involving helicopters doing commercial aerial work in Australia. This excludes incidents during pilot instruction, business travel, sport and leisure flights and general aviation activities. This is almost 200 incidents (10 per year on average) just in aerial work where UAVs could be providing a safer service delivery model.

29 of these incidents resulted in serious injuries and 21 resulted in the death of the pilot and/or passengers on board.

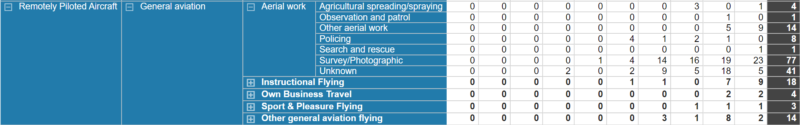

Now let me be the first to point out that UAVs (drones or RPAS) are not free of incidents either. Over the same 10 year period, remotely piloted aircraft performing similar aerial work were involved in 146 incidents. Pretty similar, yes? Especially since they’ve only really been doing this kind of work for since 2013 and most of the incidents were in the last 5 years of the 10 year period.

But the truth of that argument lies in the detail. There were ZERO fatal incidents involving UAVs from 2010 to 2019. None at all. Not only that, but there were ZERO serious injury incidents involving UAVs during the same 10 year period. None. Nada. Zilch. In the interests of full disclosure, there was one incident in the “Survey/Photographic” category in 2014 that caused a minor injury. Just the one.

Can UAVs compete directly with helicopters in aerial work? You bet they can, and they do. Every year, more and more companies walk away from helicopter-based inspection and surveys in favour of UAVs. And it’s happening largely from the top down, driven by the increasing need for publicly-traded corporations to show an increasing commitment to safety in their operations.

At the moment, the artificial limitations imposed by CASA (the airspace regulator) on UAV operations means that UAVs are not entirely able to compete in an even playing field with helicopters. But that’s mainly because CASA and Air Services Australia, who create the rules, say that UAVs, can’t fly near or over people on the ground, can’t fly over busy roads, can’t fly over urban neighbourhoods, can’t fly near towered airports, can’t fly beyond visual line of sight … well mostly, there are safety cases to be made for some or most of these situations, but the requirements are often far more complicated and onerous than those imposed on helicopter pilots. Does that have anything to do with the background of the decision-makers in CASA and Air Services Australia? I could not possibly say.

Helicopter pilots will probably argue that they have to prove that their aircraft are airworthy on a regular basis, and that’s why they don’t have the same rules. That’s true, but it does not stop them from crashing. As there is no model for UAV airworthiness certification in Australia (back to you CASA and ASA), it will take a while to defeat that argument entirely. I believe that UAVs can be made airworthy and that an annual airworthiness inspection program for UAVs would be a positive move. Not sure why it hasn’t happened already.

Helicopter pilots might argue that they have to file flight plans with Air Services Australia so that they won’t conflict with other manned aircraft. That’s true too, but there is nothing at all stopping UAV pilots from filing flight plans, only that the mechanism really doesn’t exist at this time (back to you Air Services Australia). Again, I believe that filing flight plans, at least for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations, would be a positive move. Again, not sure why it hasn’t happened already.

Helicopter pilots might argue that they have more regulatory constraints on their flight operations than UAVs, but that’s a fatuous argument because they are both heavily regulated and it’s a fact that helicopter pilots often fly outside the approvals given for their flight plans, especially in respect of altitude, and that a lot of helicopter flights in rural and remote areas don’t have flight plans.

Not only don’t they have flight plans, but often they are not monitoring the ADS-B transmissions of other manned aircraft, and they are not using the aviation radio channels intended to alert other airspace users of their flight paths and intentions. In most cases, small helicopters operating in remote areas don’t transmit an ADS-B signal either, so the only time you can become aware of them is when they fly in fast and low over your head, often taking shortcuts over private property to reduce fuel costs.

Helicopter pilots might even argue (and I might even agree with them) that the sky is made more dangerous now because of recreational drone users who don’t need a license, don’t need any training, don’t bother to read learn how to fly their drones safely, etc. I can’t argue with that as it affects my own work more often than I care to admit, but we don’t just let anyone pop into Hardly Normal and buy a helicopter to fly around the neighbourhood without a license. Nor should we allow it with drones. There are ways for non-commercial pilots to safely fly helicopters and light aircraft through aero clubs and the like, even to build and fly their own aircraft if they so wish. The same is slowly evolving for recreational drone users with mandatory drone registration, mandatory training for commercial use (even of small drones) and greater freedoms for drone club members than for the average drone operator. We just need to regularise the system so they are treated in the same way as recreational manned aircraft pilots.

Anyway, enough of my rants about how unsafe helicopter operations can be (and isn’t that reflected strongly by the fact that about 50% of all helicopter incidents in the 10 year reporting period were cattle mustering and agricultural spraying operations).

Let’s get back to the point.

Yes there are still limitations on how well UAVs can compete with helicopters in commercial inspections, aerial photography and aerial surveying operations, but these limitations are largely (if not entirely) regulatory … not technical … nothing to do with the capabilities of remotely piloted aircraft or their pilots. Just that the rules get in the way.

Even leaving these limitations aside, UAVs can and do compete very well with helicopters in most aerial work. Helicopters are expensive to deploy, expensive to operate and often require multiple crew members to conduct these kinds of operations.

Yes, helicopters can cover a lot ground in a day at 2000 feet than a UAV can at 400 feet, but there are now UAVs more than capable of operating at 2000 feet at well, which can cover the same amount of ground in the same time, at a lot lower cost.

Mobilisation costs for helicopter and light aircraft surveys are very high, as are the processing costs. It’s hard to mobilise a manned aircraft for an aerial survey for less than $50,000 and it can take weeks to arrange a survey … but you can get an equivalent UAV LIDAR survey from Queensland Drones for about half that cost and we’re typically on-site in a few days.

Yes, helicopters can fly all day on a single tank of fuel (well, arguable but let’s agree for the sake of argument), while UAVs are limited to flight times of typically less than one hour. But helicopter fuel is getting much more expensive – fuel costs have almost doubled in the past two years – and UAVs are achieving greater and greater endurance – one US-made petrol/hybrid VTOL (Vertical Takeoff and Landing) UAV has an endurance of more than 10 hours of continuous flight at 60-90 km/h, carrying commercial payloads of up to 7 kgs … and it uses a fraction of the fuel of a helicopter flying for the same period. Not only that, but if it’s petrol engine happened to fail, it has a battery motor backup that can still land it safely with little or no risk of incident.

I could go on and on (you might say I already have), but the arguments for helicopters over UAVs are becoming less and less valid, more and more reliant on archaic rules and regulations which are arguable intended to protect the manned aviation sector.

It will be the UAV sector, as I see it, that eventually manages to create a safer airspace environment where UAVs and manned aircraft can safely coexist. Along the way, it will create a safer environment for manned aviation too, resulting in fewer and fewer manned aviation incidents, especially those resulting in severe injury or death.

This will come about through the promotion of integrated airspace models where UAVs and manned aircraft fly in different altitude layers, rarely risking conflict at all. It will come about through the development of integrated airspace management models where unmanned and manned aircraft are always aware of each other and any potential for conflict can be easily mitigate by real-time communication. But in the end it all hinges on the willingness of government to examine the rules and regulations and objectively decide what needs to stay and what can be relaxed or removed entirely, as is already happening in the USA and Europe for example.

Unmanned aviation will come to dominate the commercial aviation market, from inspection drones to delivery drones, to surveillance drones, to policing drones, to remotely piloted taxis, remotely piloted cargo planes, remotely piloted military aircraft and, eventually, remotely piloted passenger flights. The future is writ large, at least for those of us reading the writing on the wall.

So the next time someone automatically assumes that a helicopter is the best option for your commercial aerial inspection, aerial photography, aerial mapping, aerial LIDAR or aerial survey project, jump in and suggest to them

“Isn’t it time we considered using drones? After all, they’re cheaper and much safer!”

To discuss more about how UAVs can deliver traditional helicopter projects sooner and safer, give me a call on 1300 025 111 or flick me an email to [email protected].