So you wanna be a drone pilot?

The Definitive Guide to Commercial UAV Operations in Australia

UPDATED 19 FEB 2020

If you are an electrical engineer or have significant experience in the electrical transmission, renewable energy, construction engineering or oil and gas industry sectors, and wanting to be a commercial drone pilot, please contact Tony (in**@***********om.au) to discuss current employment opportunities in Qld, NSW and Victoria.

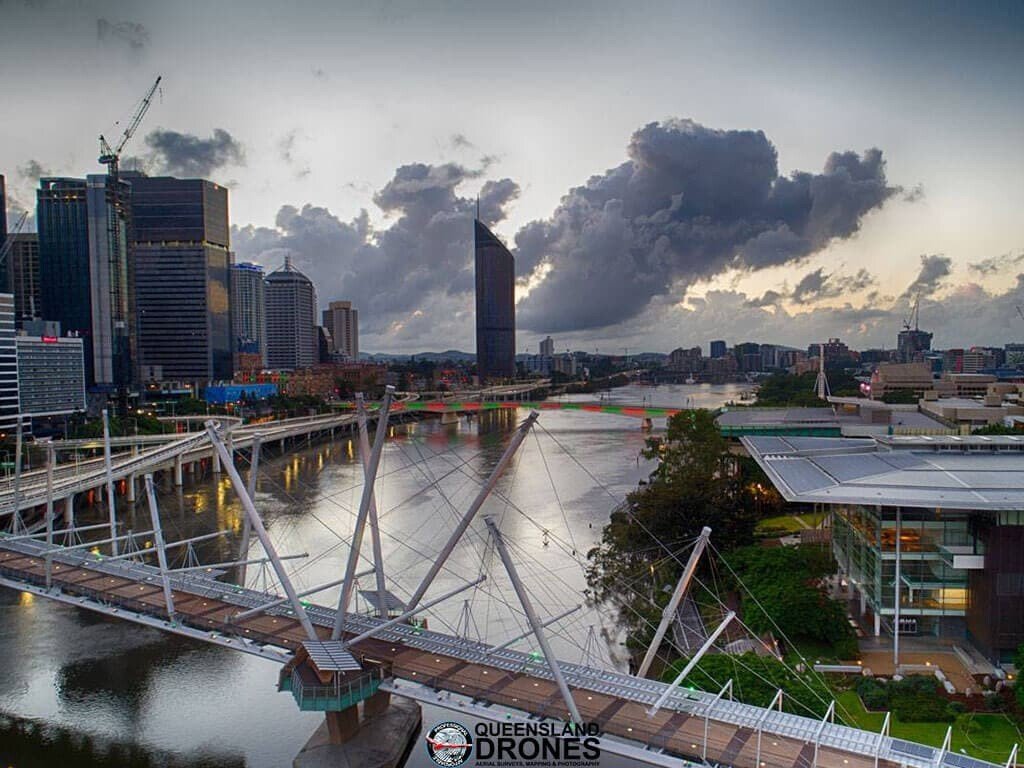

If you’ve arrived at this page looking for professional aerial imaging and aerial mapping services, please take a look at our list of Services to find out more about Queensland Drones or Contact us for an obligation-free discussion about your needs.

I wrote this post because so many people think it’s easy to become a drone pilot and waste a lot of money and time before they discover how tough it really is to be successful in this business. Queensland Drones is now in its fourth year in business and although we are well established, it’s still a struggle to maintain a steady flow of paying work. We’ve had a lot of false starts and a lot of changes of direction to reach the position we now occupy as a specialist in aerial mapping and surveys. We do still provide some aerial photography and aerial video services, but these are not our main line of business.

What you probably don’t realise at this point is that there are now more than 12,000 people in Australia holding a Remote Pilot’s Licence (a RePL, the basic qualification for a drone pilot). There are many tens of thousands more who are operating in the “Exempt” category, flying drones weighing less than 2kg, with restrictions on where they can fly, but also providing aerial photography services commercially. I’m not here to tell you not to become a commercial drone pilot, but at least go into it with your eyes open wide.

What you probably don’t realise at this point is that there are now more than 12,000 people in Australia holding a Remote Pilot’s Licence (a RePL, the basic qualification for a drone pilot). There are many tens of thousands more who are operating in the “Exempt” category, flying drones weighing less than 2kg, with restrictions on where they can fly, but also providing aerial photography services commercially. I’m not here to tell you not to become a commercial drone pilot, but at least go into it with your eyes open wide.

The truth is, it’s easy to buy a DJI Inspire or a DJI Mavic 2 and take pretty good quality photos and videos – this is what these drones are built to do. You can fly the Mavic 2 as an “Exempt” class pilot commercially (more about this below) but to fly the Inspire professionally you will need a Remote Pilot’s Licence and a Remote Pilot’s Operating Certificate (an ReOC) – again, I’ll talk more about this shortly.

Simply buying a good drone does not make you a commercial-grade drone operator, any more than buying a good camera makes you a professional photographer. There is a huge gap between what you can do with drones and what you need to be able to do to in a drone business.

In reality, less than 20% of what we do involves flying drones – the rest of our time is spent making sure we don’t break the law, making sure we don’t lose drones through carelessness or poor maintenance, making sure we limit the risk of someone getting hurt or even just annoyed by our drone flights, understanding the customers’ needs fully, writing proposals and quotes, planning our flights to achieve the customer’s goals, processing the imagery we capture to deliver what the customer wants, and following up to make sure they customer is happy and we get paid.

Processing imagery is by far the biggest part of our work. If we are capturing aerial photos, for every hour in the air we will spend an hour or two back at the office processing and editing the photos we’ve captured and making sure they meet the customer’s expectations. We’ve invested a large amount of time and effort into understanding colour grading, high dynamic range (HDR) photo capture, exposure bracketing, framing photos, managing light conditions and more to achieve the best outcomes we can for each aerial photo we capture. But the majority of drone operators work in the aerial photography space, so it’s extremely competitive. Winning jobs is hard and often the rates are very low – we know of real estate drone operators struggling to earn the same hourly rate as a checkout operator in a supermarket.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZZCTrri_xk[/embedyt]

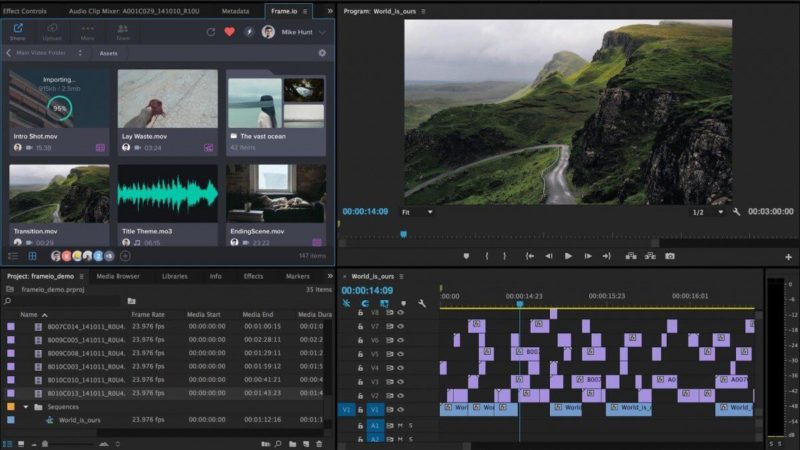

For video projects, every hour of video we capture requires about 3-5 hours back in the office for editing, colour grading and production of a finished video which often requires titling and captioning as well as music or voice overlay. Capturing great video requires even more study and planning and careful execution, compared to capturing photos. 60 minutes of good video typically becomes five minutes of finished, edited video.

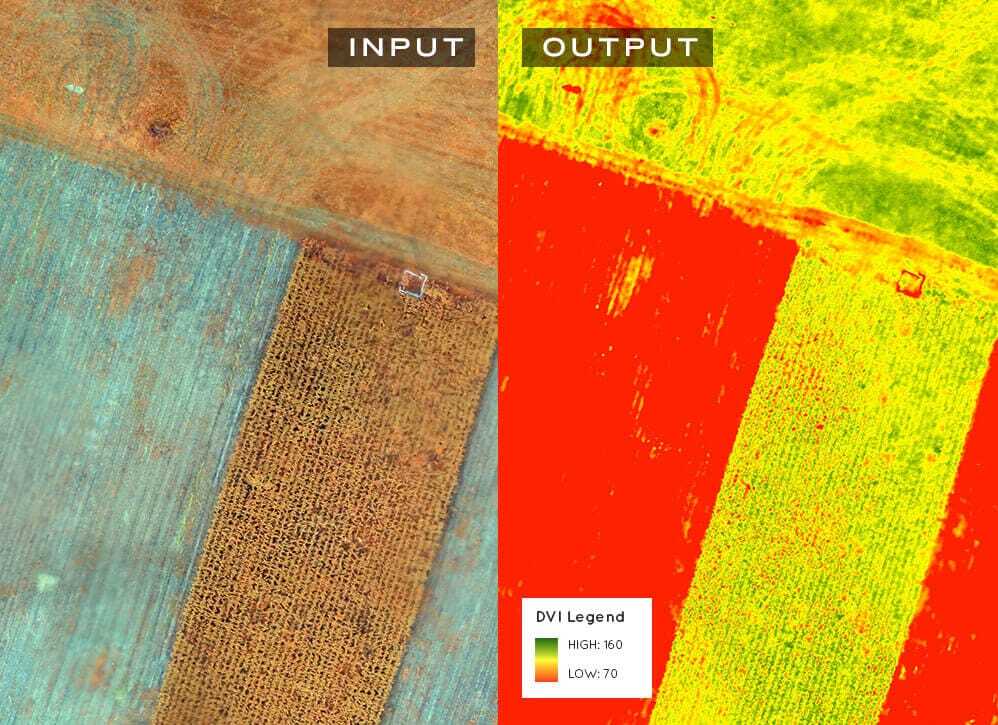

Much of our early work was done in crop health mapping for farmers and agronomists. This is promoted as easy work, only requiring that you spend as much again on specialist sensors and specialist processing software to capture near infrared (NIR) photos and process them into normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) crop health maps.

Securing a foothold at any level in the agriculture sector is not a short term activity. It takes meeting you at least 5-10 times before farmers even begin to trust you and accept that you are not going to just take their money and run, as so often happened in the past. This means lots of free demonstrations, field days, farm expos, referrals and working to build strong relationships with the people the farmers already trust, like agronomists and seed suppliers and farm support groups. It’s a very long road to travel, only to discover that in reality the farmers already have far more data than they can reasonably use on their farms and are mostly quite happy to operate on their instincts, honed over long years of crop successes and failures. Only then do you discover that the satellite industry was here long before you with NDVI and also failed to get farmers to make any significant investment in the technology.

Securing a foothold at any level in the agriculture sector is not a short term activity. It takes meeting you at least 5-10 times before farmers even begin to trust you and accept that you are not going to just take their money and run, as so often happened in the past. This means lots of free demonstrations, field days, farm expos, referrals and working to build strong relationships with the people the farmers already trust, like agronomists and seed suppliers and farm support groups. It’s a very long road to travel, only to discover that in reality the farmers already have far more data than they can reasonably use on their farms and are mostly quite happy to operate on their instincts, honed over long years of crop successes and failures. Only then do you discover that the satellite industry was here long before you with NDVI and also failed to get farmers to make any significant investment in the technology.

Given that the aerial photography, aerial video and crop health mapping aspects of the drone business are not where you’re going to make a good living, at least not in the short or medium term, you might notice that a lot of businesses like ours are doing well out of aerial survey mapping. What you need to know before you try to go there is that this is a high-risk part of the UAV business where a small error that might cost you a re-work in the aerial photography sector can quickly become a multi-million dollar lawsuit in the construction or mining sector. Customers in this sector rely on your professional expertise to verify that what you are providing is accurate in every respect, and I’m sorry but for the most part just having a drone and a subscription to DroneDeploy or Pix4d won’t take you there.

Take take a leading position in the aerial survey mapping sector, Queensland Drones has invested heavily in precision GNSS GPS equipment including PPK rover units for our quadcopter and fixed wing UAVs, plus PPK base and rover GPS units for establishing precise ground control point positions to anchor our mapping across large areas and demonstrate the accuracy of our positioning. We have also employed the services of not just qualified pilots and experience data analysts, but highly qualified GIS Mapping specialists who add to our capability to process the mapping imagery and build the kinds of outputs surveyors and engineers want, in the formats they require and to the precision levels they demand.

So here’s a no-holds barred look at what it really means to become a professional drone pilot in today’s market.

The naked truth about the commercial UAV business

About once a week I get someone calling me wanting to know how to get into the drone business. Almost 4 years since we first put the building blocks in place for Queensland Drones, I thought it might be a good time to reflect on our journey so far and provide some insights for wannabe commercial drone operators about how this business really works.

The UAV industry has grown like crazy over the past four years, from around 200 businesses with UAV Operating Certificates when we got our first commercial drone, to maybe 600 or more now, with and over 12,000 licenced drone pilots (RePL holders) competing for jobs … that’s not counting the tens of thousands of “sub-2kg” operators and farmers who don’t have any kind of licence.

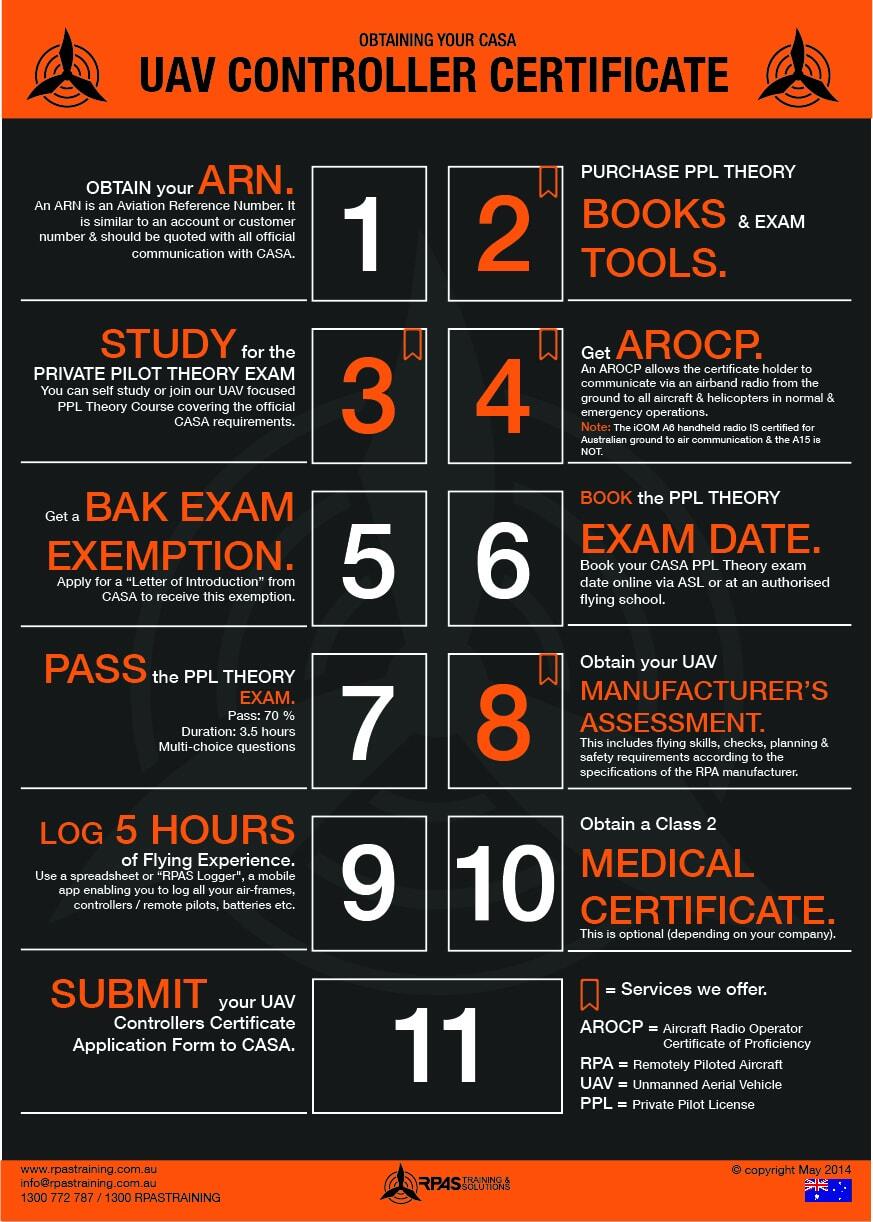

When we first started our journey you needed both a UAV controller’s certificate (pilot’s licence) and a UAV operator’s certificate (operating authority) to fly a drone commercially. But a year or so later CASA added two new categories that don’t require any training or licensing … people with “micro drones” under 2kg take-off weight who only need to notify CASA of where they are operating, and farmers who can now operate drones up to 25kg on their own farm without any notification as long as they are not being paid to operate them.

Needless to say this was not a popular decision and many commercial UAV operators are still very angry with CASA for what they see as a betrayal of the regulated operating environment in Australia. Some drone operators had spent well over a year and well in excess of $10,000 to become CASA-approved for commercial UAV operations, not to mention $20-30,000 and more on equipment, only to find themselves competing with part-timers who bought a $1000 drone at Harvey Norman.

The state of UAV licensing in Australia

When we were first starting out in the UAV business, there was only only one path to becoming a commercial drone operator, which is described in the infographic above. It was complicated, time-consuming and very expensive. It was skewed toward existing commercial aircraft pilots and closely followed their licensing model.

There are now effectively three ways to operate as a commercial UAV business in Australia.

Option 1 – Becoming a Commercial UAV Operator

First, you can go down the traditional path of spending around $3-4000 on training to get what is now known as a Remote Pilot’s Licence (RePL), then spend another $15-2500 and several months going through an assessment process with CASA to be granted an RPA Operator’s Certificate (ReOC).

You need to have written comprehensive operating and maintenance manuals, have developed and implemented a job safety assessment and risk management system, keep written logs of all your operations and be re-assessed by CASA on a regular basis to keep your OC.

These operators must carry public liability insurance and operate within strict regulatory guidelines. They are subject to routine audits and CASA may demand to see their risk management plans and flight plans at any time.

Option 2 – Working for a Commercial UAV Operator

The second option is to spend $3-4000 on RePL training and then go to work for a business that already has an ReOC. This has been a popular option for many part-time drone pilots who just want to be able to make some money in their spare time or sell their photographs online. The responsibility for their operations and the cost of public liability insurance is carried by the ReOC holder, who must keep records of their operations, ensure they operate within the terms of the OC operations manual and risk management system, and be liable if they do anything wrong.

Some RePL holders work as employees of the ReOC holder and are paid wages, while others work as associate contractors and pay the OC holder a monthly fee and/or a percentage of their earnings. Operators under both these options can fly larger, more sophisticated UAVs with weight limits up to 7kg, or even 25kg in some cases. They often have blanket permission from CASA to operate within 5 km of unmanned airports (under strict guidelines), to operate within 15m of people and buildings (under strict safety rules) and to fly after dark (under strict safety rules). They can apply to CASA to fly within the restricted spaces of major airports and even to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS), based on strong safety management processes.

Option 3 – Working in the “Exempt” Category

The third option – the most popular and most controversial – is to only use drones under 2kg, like the popular DJI Phantom range, and simply register your intention to operate commercially in a specific area with CASA and agree to operate within CASA guidelines. These notifications are valid for up to two years.

Sub-2kg operators, as this third group are known, have to operate within strict standard operating conditions:

- They must keep their drone close enough at all times to be able to fly it manually if required

- They cannot fly more than 120 metres (400 feet) above the ground

- They can only fly during daylight hours

- They must keep at least 30m away from people (and not fly over them)

- They cannot fly within any restricted or prohibited area or within 5.5 km of a towered airport

- They cannot fly in the approach, departure or movement areas on untowered airports or where they might create a hazard to aircraft

- They cannot fly in populous areas (ie, where a loss of control might cause hazards to people or property)

- They cannot fly in areas under emergency services control (e.g. near police and fire operations)

- They can only fly one drone at a time

- They cannot apply for any conditional approvals (like BVLOS, operations after dark or flying near towered airports)

Most sub-2kg operators cannot get public liability insurance, which means they cannot perform work for major companies and government organisations who usually require such insurance for any UAV operations. If they injure someone on your property or damage your property (or someone else’s property) while working for you, it is possibly you could be held vicariously liable for their actions, especially if they are unable to pay damages themselves.

The above is not meant to be a comprehensive or exhaustive coverage of UAV licensing, just a summary. Refer to https://www.casa.gov.au/aircraft/landing-page/flying-drones-australia for the latest and most comprehensive coverage of UAV laws and regulations.

The state of the UAV industry in Australia

It’s still tempting to think that buying a drone and flying it commercially is some kind of get rich quick scheme, or at least a way to toss off the yoke of a 9-5 job and do something you really enjoy for a living. It’s true that some UAV operators are achieving that goal, but they are in a minority.

There is no “drone boom” in Australia. Interest in using UAVs commercially is certainly growing and we get more enquiries (and more types of enquiries) every day, but it is not growing at anything like the rate of creation of new UAV businesses in this country. You will not find people beating down your door to hire your drone, and most of the people who said they’d love to buy your aerial photos most probably won’t do so.

The UAV industry in Australia is shaping up like most other highly competitive business sectors (see Marketing 101 for more information). There are a small number of very successful operators who employ dozens of pilots and have invested millions of dollars in their operations to get to where they are today. Most of these operators have been in business for many years. At the other end of the market are literally thousands of small operators, some licensed and most not, who are competing for a very finite market filming weddings and real estate videos. In the middle are the usual array of wannabes and niche operators who either have plenty of capital to build a business that will compete with the big players one day, or are focusing on specific drone activities requiring greater skills and knowledge.

Commercial drone operations is a knowledge-intensive and capital-intensive business. If you are not learning new skills all the time, developing advanced techniques and buying the latest drone and photographic technologies, you get left behind very quickly. If you’re a guy with a DJI Phantom and a passion for flying it, and not much more, you can set yourself up very cheaply as a sub-2kg operator but you’ll very quickly get left behind in this business. And if you happen to damage or lose your DJI Phantom, you’re out of business entirely until it’s repaired or replaced.

Even operating under sub-2kg rules, you’ll very quickly discover that you have two choices – either you operate illegally (outside the law) or you operate within a regime that has many rules and many competitors who will report you the moment they see you breaking those rules. For example, you need land-owner permission to fly on any private property, you need council permission to fly in most parks and reserves, and you need government agency permission to fly in forests and national parks, which includes most beaches. You can’t just over-fly roads, footpaths or neighbours’ homes to get to your destination or to get that great angle.

That drone you bought last year, the one you had to convince your wife would make you more money, was pretty much outdated by the time you got it out of the box and into the air. For example, if you bought a DJI Phantom 4 for $1600-2000 last Christmas, you might be shocked to know it’s already been discontinued. Two more models have been released since then, with better cameras and more features, and another is poised for release any day now that will eclipse both of those. If you’re still trying to compete with that Phantom 3 Pro you spent $2500 on a year ago, you might already be finding that operators with newer drones like the Phantom 4 Pro or the DJI Inspire are wowing your potential customers with 20 megapixel photos and 4K video to 6o FPS.

It’s not just about flying a drone

The big fallacy in the commercial UAV business is that it’s about flying a drone and making money from it. After 18 months in this business I can tell you it’s not really about either of those things. It’s about being able to offer a product that provides a value that significantly outweighs its cost; it’s about being able to deliver that product efficiently and consistently within strict rules; and it’s about being able to run a business (manage your costs, pay your bills on time, meet reporting requirements, etc). And that’s without even thinking about all the additional rules and reporting requirements of operating as an ReOC holder or even as an RePL holder under someone else’s OC.

When I first started in this business I liked nothing more than getting out every spare minute I had to shoot spectacular sunrises and sunsets, capture amazing panoramic vistas and film stunning nature videos. That’s why I got into this business and it’s what I thought this business would be about.

I’m one of the “lucky ones” who’s managed to walk away from the drudgery of my desk job (and, as my wife might say, my $120,000 salary and benefits) to go full time in the UAV business. I’m the only one from my UAV pilots’ course last year who has managed to do that! So am I having fun yet?

These days I’m spending 20 hours a week on business development to make sure I have enough work to do next month; 20 hours a week sending out invoices, chasing payments, paying bills, doing BAS returns and maintaining tax records and 20 hours a week worrying about land-owner permissions, insurance notifications, CASA permission requests and completing flight reporting and aircraft maintenance routines. All that is before I get to fly an hour! By the time I’ve flown 10 hours capturing images and data, I have around 30 hours of image stitching, video editing and post-processing (much more if I’m doing ortho-mapping or 3d models) and another 10 hours each week of to and fro with clients making sure they’re happy. I also need to find time to attend and exhibit at field days and expos, attend and sometimes speak at industry events, conduct client demos and occasionally fraternise with my competitors.

Do I still find time to nip out and capture a stunning sunset? Not lately. Not even on the weekends as that’s precious time to spend crawling over Youtube videos and Facebook posts in professional UAV groups looking at what others are achieving and figuring out how they did it, trolling the technology sites to figure out what the “next big thing” will be to maintain my competitive edge, doing online training, updating mission control software and testing it for bugs, charging batteries and maintaining aircraft, and on and on it goes.

Do I still love what I do? Hell, yes, but not for the reasons I originally thought I would. I love it because I have a passion for running my own business (this my third or fourth, depending on how I count them). I love it because it challenges me every hour of every day to be the best I can be and to apply every bit of knowledge and experience I’ve acquired across my life to stay ahead of the pack. I love it because I find I can do things that 98% of people can’t. And I love it because what I create makes such a difference to my clients and their businesses.

And it’s not about flying a drone either

Looking in from the outside it’s easy to think that all we do is fly drones. But if what I’ve described above hasn’t told the full story, let me make it really, really clear. Flying drones is only a small part of what we do as a commercial UAV operator.

Before we ever get to fly a drone, we first have to find and win the business. This means spending many hours every week making phone calls, responding to emails, attending meetings, doing presentations, writing proposals or quotations, chasing them up, securing required permissions and doing job safety assessments.

We also carefully plan each flight in our mission planning system before we leave the office to ensure we know exactly how the job will be conducted, how many staff will be needed to ensure safety, what equipment we’ll need to take and how long we’ll be on site to capture what we need to meet client expectations. This includes carefully checking and rechecking weather forecasts to make sure we’ll have enough light and not be socked in by cloud or rained out. We also need to check airspace maps to see what else is going to be in the air around us.

For most jobs we need to travel to and from the client’s location, which can often be two or three hours away – sometimes much further. This means before we leave the office we have to check all our equipment to make sure it’s complete, correctly maintained and ready for use (which includes UAVs, batteries, spares, laptops, tablets, radios, cables, etc, etc), grab any extras we may need for a long day like a generator, inverter, battery chargers, icebox, drinks and snacks, pack all of this into our truck and figure out how we’re getting to the job (including traffic in many cases).

We typically plan a full day’s flying to get the most out of the weather, leaving around 5 AM and getting back around 6PM. For more remote or distant locations we might plan two or three days flying which may mean we have to plan airline flights, equipment shipping, car hire, accommodation, etc.

When we get to a job site, we need to spend time chatting to the client, setting up our equipment, unpacking and checking UAVs, doing site safety inspections, assessing and mitigating risks (which often include people walking through, animals that may intrude into the site, low-flying aircraft and helicopters, trees, hilly or mountainous terrain, tall buildings and other obstacles, flight paths, take-off and landing areas, etc), setting out safety equipment (like reflective cones and tapes), and organising staff in roles like spotter, radio operator, safety monitor, etc.

For really specialised jobs we may need to be laying out ground control points (GCPs) to improve our positional accuracy and working out things like cross-grids and oblique grids to capture all the images we need for 3D models and maps. We may also need to choose which cameras we are using, which filters are being used on each camera, etc.

Once we’ve done all that, we can put our drones in the air and do the fun stuff. It is still fun after all that, isn’t it? Surely. As we fly we need to monitor the area for possible intrusions, monitor the radio for air traffic, monitor the UAVs themselves for system integrity, battery life, etc., and make sure everyone is doing their job properly. We also need to make sure the UAVs are capturing the data we need during and after each flight, plan safe landings, log flights, check aircraft for any damage or issues, pack everything up, chat to the client and then head home.

When we get back we need to return all our checked out equipment to storage, checking every item to make sure it is complete, undamaged and not requiring monthly or quarterly service inspections. We need to file our flight logs, permission forms and safety assessments, then we can get down to creating something special.

To do that we need to transfer all the captured flight data to our office computers, back it up to the cloud and start dissecting and processing it to get to what the client actually expects to receive … which may be normal or panoramic photos, edited video, an orthographic photo, a contour or elevation map, an NDVI crop health map, a volumetric estimate of a stockpile, a 3D virtual model of a building or land area or lots of other possible products.

For photography missions this may include checking each photo to see which are the best post-processing candidates, combining multiple exposures of the same scene (AEBs or HDRs) into single photos, combining multiple finished photos into panoramic views, colour-grading images, cropping images and exporting them to formats that meet client needs. The images then need to be uploaded to the cloud where the client can inspect and download them.

For video missions it may mean selecting video sequences, editing them to find the best and highest impact segments, stitching them together to create continuity and working out the right transitions between scenes, editing again to get to the length the client expects, colour-grading and possibly speeding up or slowing down some segments, choosing appropriate background music, building titles and captions, then exporting the video into a format the client can readily use and uploading the finished video(s) to the cloud for the client to view and download.

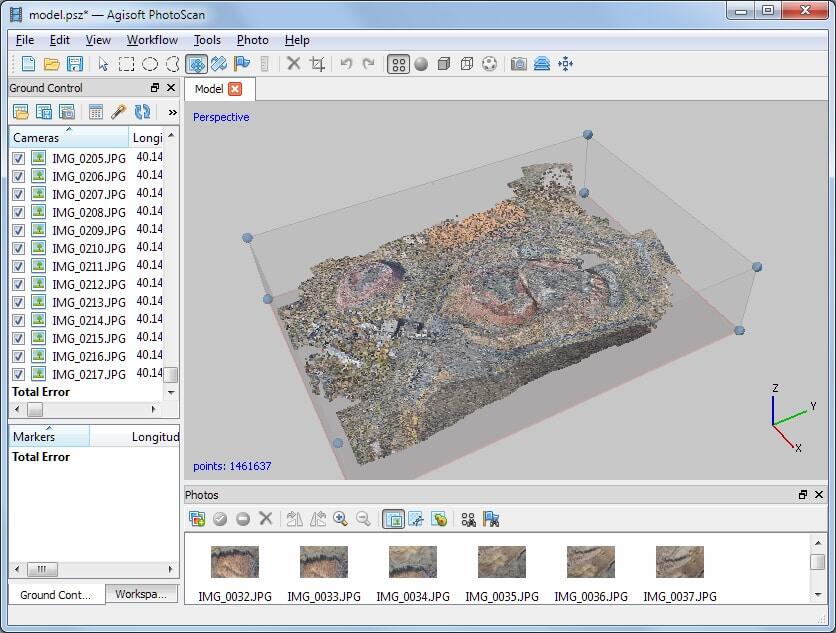

For mapping missions we may need to stitch hundreds of overlapping images together into a single, very large orthophoto, edit and clean many hundreds of points in a point cloud to ensure we are only using the images that will contribute most to the finished product, then building textures, 3D models, NDVI maps or what ever it is the client needs to inform their project.

After all that is done and the client has what they need to move on with their project, we still need to worry about recording our expenses for the day, making sure vehicle logs have been completed, enter times and costs into the accounting system, generate a tax invoice and job report and get those out to the client so we’ll get paid!

So as I’ve said a couple of times above, it’s not really about flying drones. That’s only a very small part of the job.

And by the way, drones ain’t drones Solly …

The skills and experience you need to be successful as a commercial UAV operator go well beyond the skills and experience you might have acquired flying your drone for recreational purposes. Those skills are useful, but they are only a very small component of what will make you successful in this business.

And that drone you thought was so expensive when you bought it? Well it wasn’t. It was so cheap it’s almost useless for most commercial UAV applications.

DJI drones are, in my opinion, great products and I have a few of them that I use from time to time in my business. But they are not the core of my operations. For serious aerial imaging projects we mostly fly fixed wing UAVs that start at around $15,000 and go way up from there.

Integrated cameras, like those in the DJI Phantom, have serious limitations. For real commercial UAV projects we typically fly with near full-sized SLR cameras like the Canon S100 and the Sony A6000, often modified for near-infrared or other specialised purposes. These cameras often cost far more than a DJI drone! In the future we will be investing in even more sophisticated cameras including thermal and multispectral cameras that may cost more than our fixed wing UAVs!

We’re still only scratching the surface of what it takes to be a serious commercial UAV operator, by the way. As we go further and further into this business, we are no longer competing with our neighbour or the kid down the road who go a drone for Christmas. We find ourselves competing with the big operators who are backed by aerospace giants and international technology companies, operating UAVs and cameras that make our equipment also look like toys.

It’s not my intention to put you off going into the drone business. But make sure you go in with your eyes wide open, know what it is you intend to achieve in the business and who your customers will be, know what motivates them to use your services and how you make a difference to their lives by what you do (that they could not do for themselves, or ask a friend to do). Make sure you have the resources to establish and maintain your business – firstly the time to be able to devote to building the business and finding repeat customers; secondly the money (capital) to invest in the right equipment, keep it up to date and refreshed, pay support staff and pay your bills; and thirdly the passion and motivation to make the jump, leave your day job and do what has to be done to make this business work, and keep working.

To my mind, there is far too much hype in this industry and not nearly enough hard, practical graft. Please feel free to ask me any questions you might still have using the comments field below.

Please note that we may receive some remuneration for sales generated from links in this article.

And by the way, if you’re a potential aerial imaging customer reading this, I hope I’ve helped you to understand why you should not expect to get your aerial photos for peanuts (unless you can get a monkey to do it).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

One Comment

Hello,

I have to say Wow! what you have written is the most comprehensive detailed description that reflects knowledge, work development ,pure passion and determination. Your experience definetly shows understanding the true depths of the aviation industry of drones that is beneath the surface.

I am interested in getting a drone licence not for commercial reasons but for public events we attend as I am part of a Kite Club. My background is Electrical Fitter Mechanic, solar and engineering technical. I am no longer interested in working on the tools etc.. I now work as a robotics engineer coach (schools) and I’ve never flown drones before but I now have a new appreciation and somewhat understanding of what it could possibly entail after reading your story. Thankyou for sharing , very interesting, entertaining and truthful…